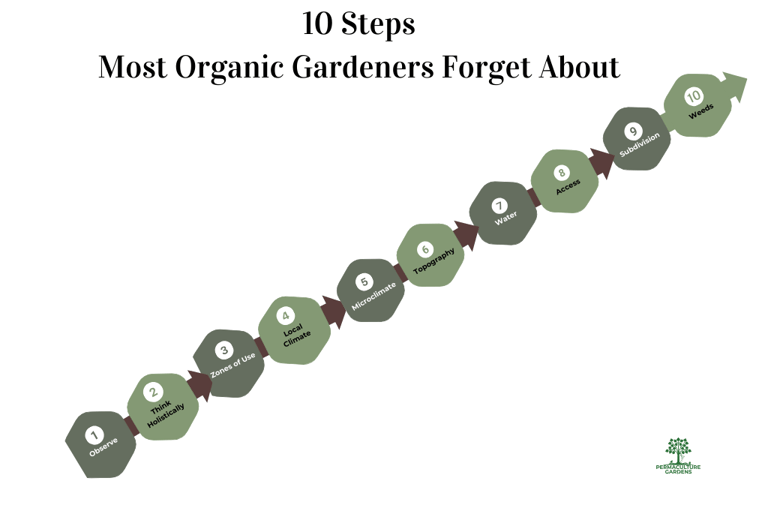

How to Plan & Design Your Permaculture Garden: 10 Crucial Steps Most Organic Gardeners Forget About

What makes permaculture garden design different from landscape design? Two things: Observation and planning We like to say, “Plan before your plant.” In this blog post, we teach you how to design your permaculture garden using "10 Crucial Steps"

2/5/202419 min read

How to Plan & Design Your Permaculture Garden:

10 Crucial Steps Most Organic Gardeners Forget About

Disclaimer

This Permaculture Design article may contain some affiliate links. The small commission we receive if you choose to purchase goes towards making this gardening education available for free! We do not affiliate for anything we do not personally use. Thanks so much for your support!

Permaculture Garden Design Video

Introduction to Permaculture Design

10 Crucial Steps (aka Scales of Permance-ish)

What makes permaculture garden design different from landscape design? Two things: Observation and planning

We like to say, “Plan before your plant.”

In this blog post, we teach you how to design your permaculture garden using the "10 Crucial Steps" outlined below based on something known as the "Scales of Permanence (more on that to follow):

1. Observe

Permaculture author, Amy Stross says, You can garden in just 15 minutes a day, seven of those minutes should be spent observing."

Embracing Imperfection

Bill Mollison, the co-creator of the word permaculture, used to emphasize that the first year on your property should be all about observation. But this doesn’t mean you can’t plant something immediately. Remember, the focus should not be on getting everything in your design perfect from the start. Trust the design process, which begins and ends with observation.

What Exactly Are We Observing & Why:

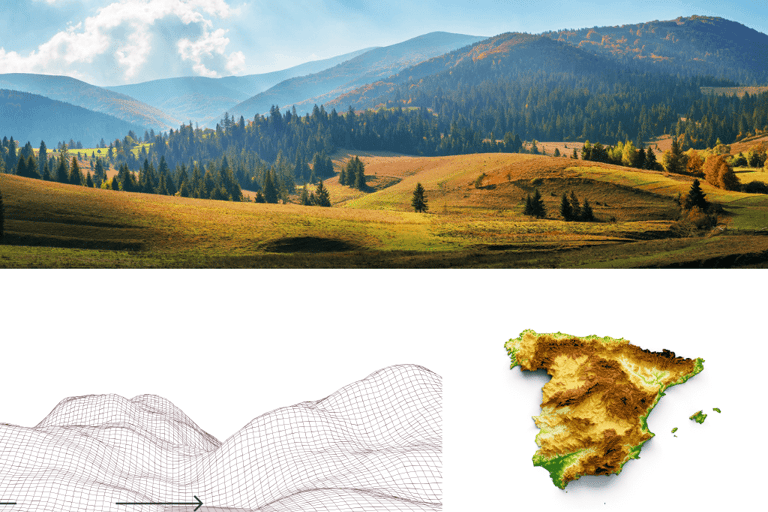

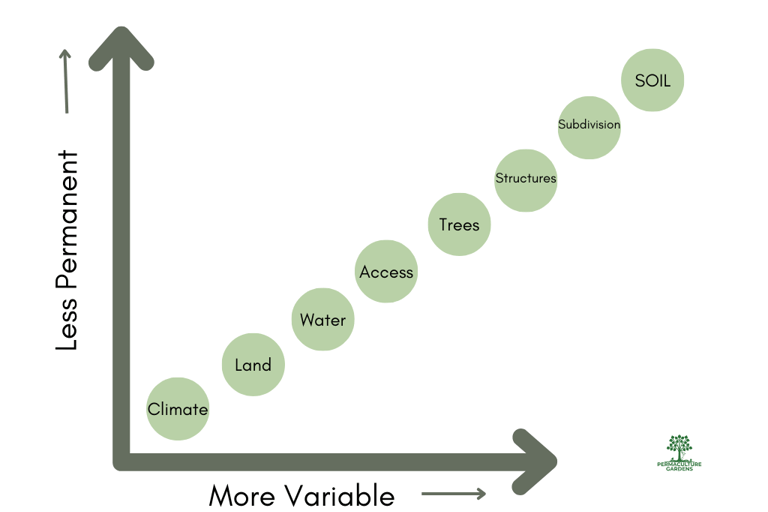

PA Yeoman’s Scales of Permanence

The "10 Steps" are based on PA (Percival Alfred) Yeoman’s Scales of Permanence, a framework for prioritizing and understanding the permanence of landscape elements. Yeomans was an Australian inventor known for his Keyline design system to increase the fertility of the land. He also invented a design methodology governed by his “Scales of Permanence.”

Yeoman's Scales of Permanence are as follows:

Climate

Landform / Topography

Water

Access

Trees

Structures

Subdivision

Soil

The image shows how we should start by considering the most permanent factors affecting our site before noting the “scales” that are less permanent and thus, more variable.

The climate is the most permanent of the scales. You can’t change your climate (except if you decide to move elsewhere). Knowing your local climate will determine what kind of buildings or structures (lower on the scales of permanence) you should build.

PA Yeoman’s Scales ends traditionally with soil, but we have dedicated an entire workshop to that topic and are not including that discussion here.

By analyzing the landscape through these scales, designers can make informed decisions leading to sustainable and resilient designs.

You can learn more about how this is applied on a large landscape like a farm from this video by Tom Ward of siskiyoupermaculture.com.

Go from Most Permanent to Least Permanent

PA Yeoman's Scales of Permanence

The 10 Crucial Steps we use for garden planning

Tips for Implementing the 10 Crucial Steps Design Formula

Stay Committed:

Take daily walks around your property for 10 minutes, making observation a habit. Use a timer to ensure consistency.

Take Notes

Journal daily, jotting down brief notes. Use the prompts provided but also make your own observations.

Choose Optimal Times

Choose optimal times for observation, considering climate variations. Involve the family in this exercise to make it a shared experience.

Use a Timer:

Stick to the designated 10 minutes to maintain a balanced routine.

Now that you know what to observe and how to do it let’s move on to the second crucial step: Thinking Holistically.

Additional Considerations

Over time, permaculture designers have developed these scales more to encompass such considerations as wildlife, economy, and community. For home gardeners who live in a community development, aesthetics is crucial "scale," since having a productive but ugly garden may mean getting cited by HOA restrictions or legalistic neighbors.

Measuring Reel

Notepad

Pencil or erasable pen

Phone Camera

Materials You Need to Observe Well

Grab your camera, measuring reel, notepad, and pencil or pen.

Measure the periphery of your yard, home, and access points.

Note down the measurements on paper or on your phone.

You can later compare these notes with a top-view Google map zoomed into your location.

Directions

The tools for garden observation are simple & easy to find

Take a step back and think what affects my garden and what will my garden affect?

How do we think holistically?

We think holistically by asking the question, “How does the thing I am observing or designing affect the whole?"

For example, you want to design a food garden. You may want that garden in your sunny yard. So you buy or build a couple of raised beds and plop them in a place that “looks nice” in your sunny yard. However, you soon realize that you never tend to visit that spot. And so the garden is neglected.

Ask yourself, “Why am I not visiting the garden?”

Is the garden too far from the house?

Is it too hot during the summer so you tend to hide indoors and forgo the “chore” of gardening?

Is there no direct path to encourage you to go to the garden?

How can you make it so that you cannot help but pass by this garden on your way into the house? How can you force yourself to garden? Here are some possible solutions:

Create an accessible pathway to the garden

Move the garden closer

Scratch the whole “garden outside” project and start by growing indoors.

Pretend you’re a drone. You inevitably find that the farther you zoom out from that small problematic area, and look at the bigger picture of your property, the more problems you can solve before they become problems.

That’s what thinking holistically does. It helps you return to the reasons you are growing food in the first place. It helps to see the forest for the trees.

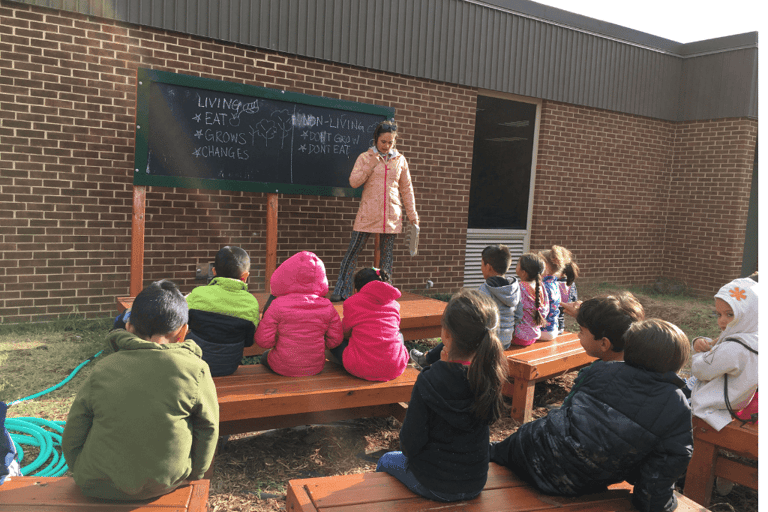

Say, for instance, you’re growing food to teach your children where their food comes from, it will be helpful to build the garden close to the outdoor swing set that the kids frequent!

Pause for a bit before reading on, and think about what other garden-related problems you need to solve.

2. Think Holistically

Teaching children where their food comes from

What to Observe: Patterns

Thinking holistically also means observing existing patterns and figuring out how to use them to achieve your overall aim of growing food. You may discover that what exists needs to be replaced with something better. But you'll never know unless you find the patterns in the first place.

In each step of the 10 Crucial Steps, you end by looking at existing patterns that nature or your actions impose on the landscape and see if you can work with the pattern, especially if they are naturally occurring, or promote other ways of solving your gardening problems.

A vegetable garden gives ample opportunity for observing patterns.

Let’s take the case of deer constantly attacking your flowers and vegetables. Start observing where the deer come from. When do they feast on the flowers? What dregs do they leave behind for you to eat?

Knowing their travel patterns, their diet, the times of day or night they are in your yard, and even their mating season, can give you insight into how to deer-proof your garden for the future.

Honestly, we have found for a “lazy gardener,” which is what permaculture gardeners are, you will have to do one or more of the following:

Invest in a fence/deer protection barrier or

Plant herbs that they don’t like eating such as basil, thyme, lavender, mint, etc.

Be resigned to sharing your berries with them and creating a deer hedge where they will browse the berry bush but cannot go through the bush to get to your vegetables.

For carnivores, shoot the deer (and eat it!)

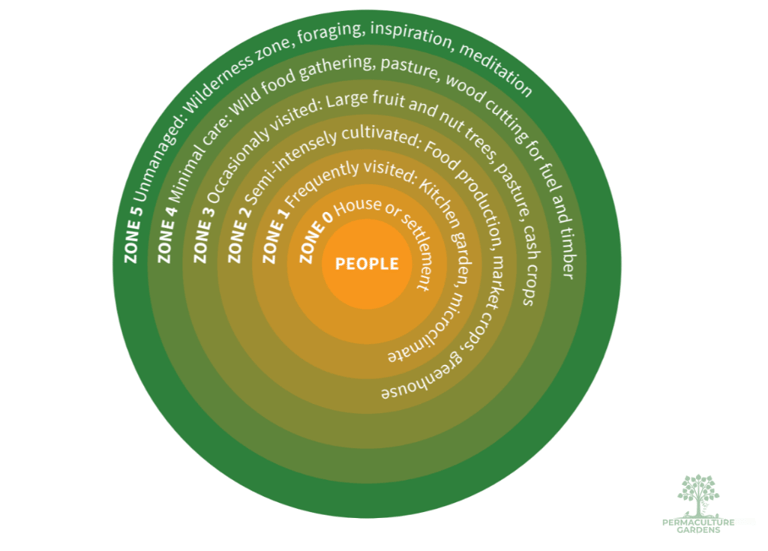

Using Zones of Use helps us plan out our outdoor spaces according to how frequently we visit them.

What is this concept of “Zones of Use?”

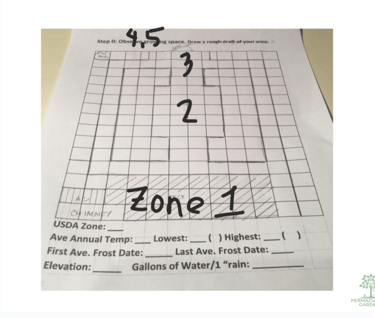

3. Know your Zones of Use

In permaculture, we can efficiently organize space based on human activity.

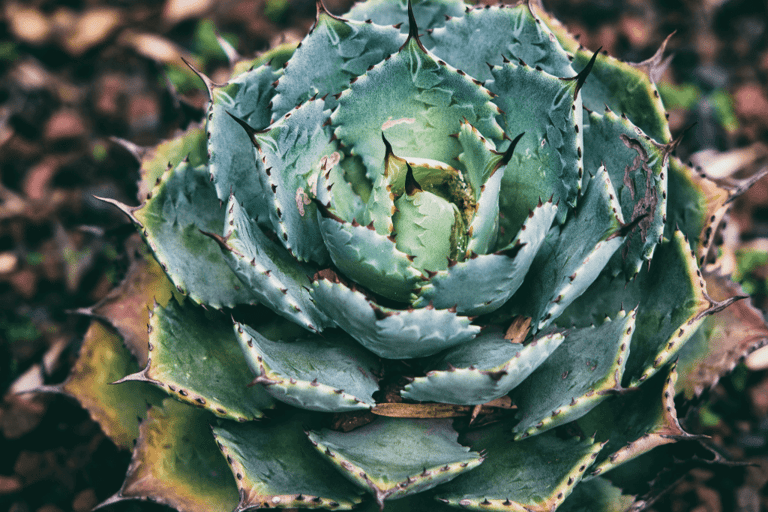

The more frequently used zones or areas should be designated Zone 0. The least frequently visited areas are labeled Zone 5. These are different from your USDA Growing Zones. Here are each of the Zones of Use followed by a brief description:

Zone 0: Home or settlement.

Zone 1: Frequently visited kitchen gardens or herb gardens.

Zone 2: Semi-intensively cultivated food production, market crops, with the possibility of a greenhouse.

Zone 3: Occasionally visited, suitable for large fruit and nut trees, pasture, and other uses.

Zone 4: Minimal care, suitable for gathering berries, pasture, and cutting for fuel and timber.

Zone 5: Unmanaged wilderness zone for foraging, mushroom hunting, etc.

Ranking the areas on our property (even within our house) according to their frequency of use allows us to design these spaces appropriately.

There is an anecdote of Bill Mollison lecturing about this by saying something along the lines of,

“When you wake up in the morning. Put on your fuzzy slippers and get some chives for your omelet. If you come back and your slippers are wet… you’ve walked too far.”

What to Observe: Zones of Use

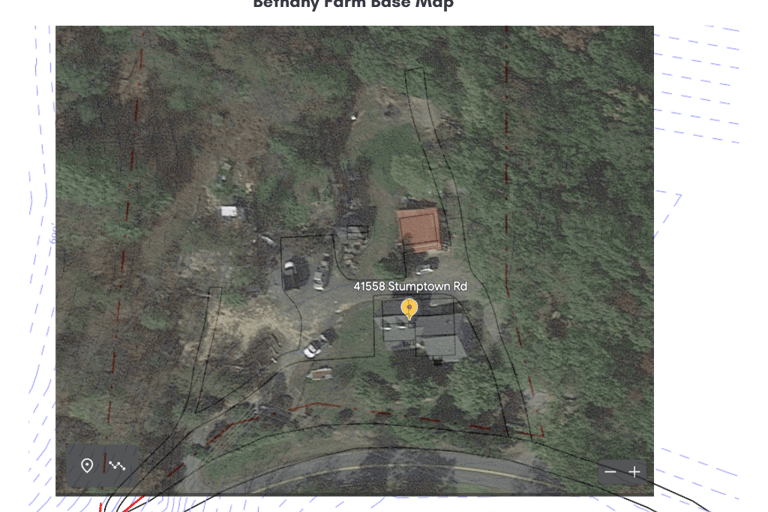

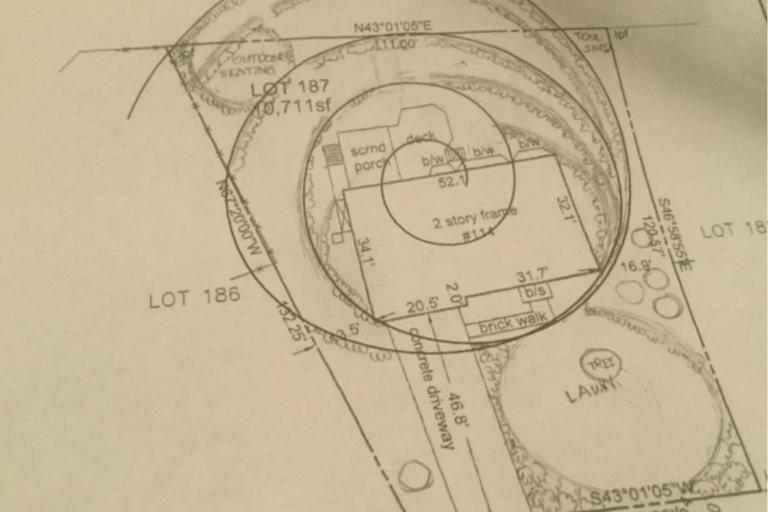

Grab your property's PLAT map (or a top-view map of your property) and take 10 minutes to observe outside.)

Come back inside and label the different areas of your property according to Zones of Use.

Here is an example of our Zones of Use when we lived in a tiny townhouse.

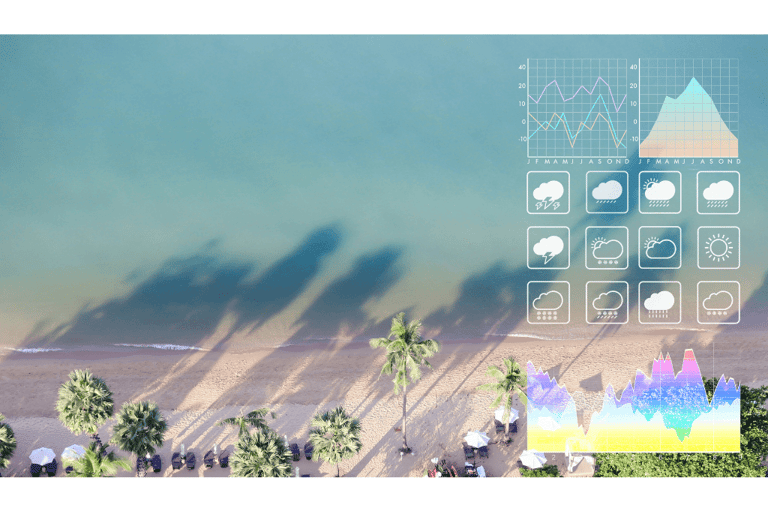

The local climate affects your growing seasons but also your overall garden design,

Factors that Affect Your Local Climate

4. Know your Local Climate

Climate encompasses the weather patterns affecting temperature, rainfall, and seasons. Other factors like elevation and proximity to a lake or ocean also affect your local climate.

Knowing our local climate includes knowing when the seasons of drought, hail storms, flooding, and much more arrive. Gardeners often pay attention to the temperature but not too often to things like hail, wind direction, and wind intensity. And with climate change, when those flash floods come, it feels all the more unexpected.

But if we tune ourselves to the current state of the local climate, we'll start saying things such as, "It has never been so warm, so early in the year, as it has been this year," without relying on news reports. It's because we notice, we are aware.

Planting By the Moon

Just as the sun warms the earth, water (as in the case of the tides) is influenced by the moon.

Over the years, gardeners have observed that moon phases also affect seed germination and growth. This phenomenon is likely due to the gravitational pull on the waters in the soil.

While the lunar effects on plant growth and development are not extensively studied, gardeners try to harness the help of the moon’s gravitational pull to ensure successful planting. (More on Planting by the Phases of the Moon in a future blog.) Suffice it to say knowing what seasons to plant certain crops comes before knowing when to plant by the moon. If we do it the other way around, we will no longer be lazy gardeners.

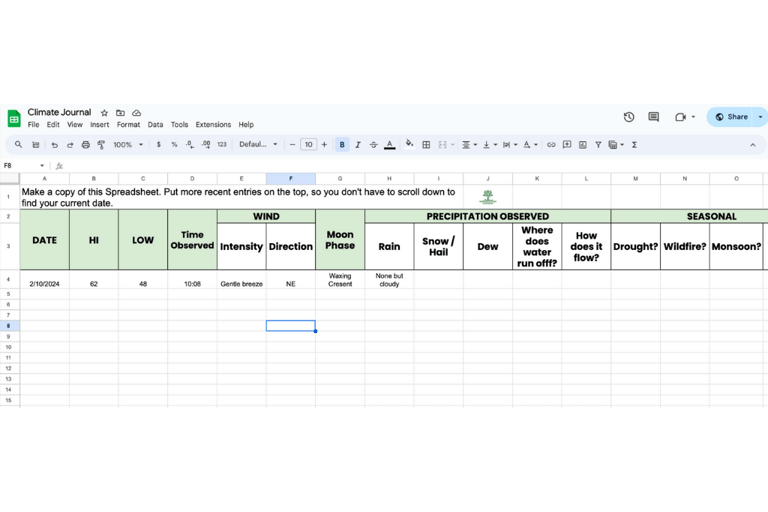

What to Observe: Local Climate

Here’s a spreadsheet you can use to observe your climate on a given day. If you do this every day for a week, you’ll start wanting to go outside more. You can also find a link to this spreadsheet from the 10 Crucial Steps Workbook that accompanies this blog.

Do this daily for a year, and you'll get an intuitive feel for climate and become a human thermometer. You’ll know what 55F /12.78C feels like just by stepping outside!

This garden journal can help you become a good observer and refine your garden plan through observing the weather.

We identified 7 different microclimates in our small townhouse garden space.

What Are Microclimates?

5. Find your Microclimates

Microclimates are places where the weather, (if it may be called that in a small location) is different than elsewhere. A microclimate is always seen in relation to everywhere else on your property. You may find a space that is too wet, too dry, too hot, too windy. Those small, unusual spaces are your microclimates.

In a tropical country such as the Philippines, someone on Instagram once shared how he could grow kale (a plant that typically dies in hot weather) under a window cooled by an air conditioning unit.

Microclimates are opportunities to extend your harvest, and grow something “out of the box” and unusual.

Your home can have several different kinds of microclimates. What microclimates can you think of in your property right now?

What to Observe: Microclimates

You can use the microclimate prompts in the 10 Crucial Steps Workbook to help you notice areas you may not have considered growing food in.

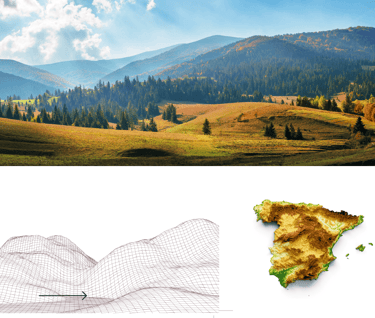

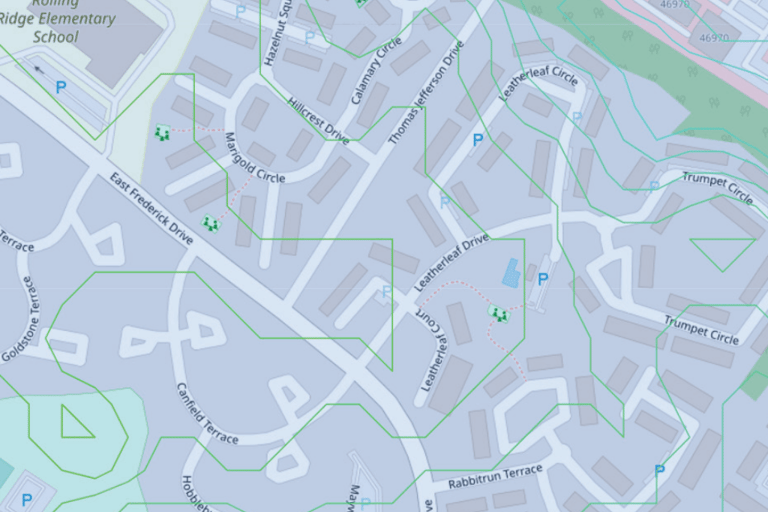

Topography influences th flow of water in your garden.

What Are Contours?

6. Note Topography

Contours are a key concept in "reading your landscape." Contours are the outlines of the mountain that are level or flat. It's there that water can stop and seep through. Think of leveling a mountain as the ancient Filipinos who built the rice terraces did.

Imagine a rimmed plate.

Now turn that plate upside down and think of it as a mountain. That rim, where everything is flat, that is what a contour is. A contour is the part around the mountain where the land is level. Note: There could be several contours higher than that rim of course. Think of the roads we use to go up the mountain. That is exactly why we build roads (or should build them) on existing contours because that is where the land is flattish.

Topography or understanding contours, ridges, water lines, and watersheds is crucial in water management because the physical shape and features of the land influence how water flows and drains. In his book “Water for Every Farm” P. A. Yeomans observed how editing the landscape can alter the direction of water.

Andrew Millison, who teaches Oregon State University’s online Permaculture course has a much better explanation of contour and its use in permaculture design.

What to Observe: Contours

There are two ways to observe contours.

1. Manually on the ground using a tool that you can put together with three pieces of wood called an A-frame and plum bob.

Here's a video of how we mapped out our garden using this data. Using an A-frame to find contours is its own article.

2. Online through GIS (Geographic Information System) data. This can be as simple as looking up your property on Google Earth or even Google Maps and clicking on terrain or topography. Or using Digital Elevation Models (DEMS) from the USGIS or Verge Permaculture's mapping services. The more data you want about your property, the more costly the services become.

Knowing about your property's topography leads us naturally to consider the 5th Crucial Step: Water

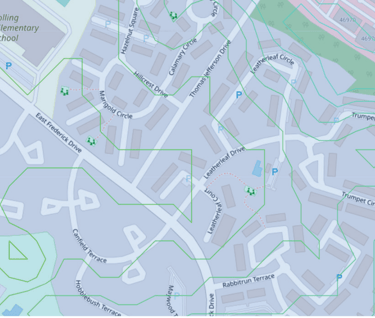

This topographic map of a housing development shows the water lines in green.

We captured the water from our downspout and channeled it away from our basement into our flower garden beds.

Guiding water where it should go

7. Channel Water

While we can’t influence the amount of rain our location receives, we can choose where to field that water when it falls.

Is your home water-logged in one area and dry in another?

It’s important to know what we want water to do. We want water to stop, steep, and slowly spread.

We can slow water flow down by changing the topography so that it doesn’t rush down a hill. We can level land along contours, and plant trees alongside a drainage ditch (which permaculturists like to call swales). But we can also capture the energy that water is. And use it so that we are less reliant on the water grid. We capture water through pipes, rain barrels, and other catchment systems) so that it seeps into our gardens and increases soil fertility instead of washing away our topsoil or flooding our basements.

Here are a few photos of ways in which we have redirected water.

What to Observe: Water flow

The best time to observe how water flows through your property is to put on a rain jacket, and rain boots and walk around your property on a rainy day.

You can download The 10 Crucial Steps Workbook for prompts to help you assess how water flows in your home and a formula to determine how much water you can capture from your roof.

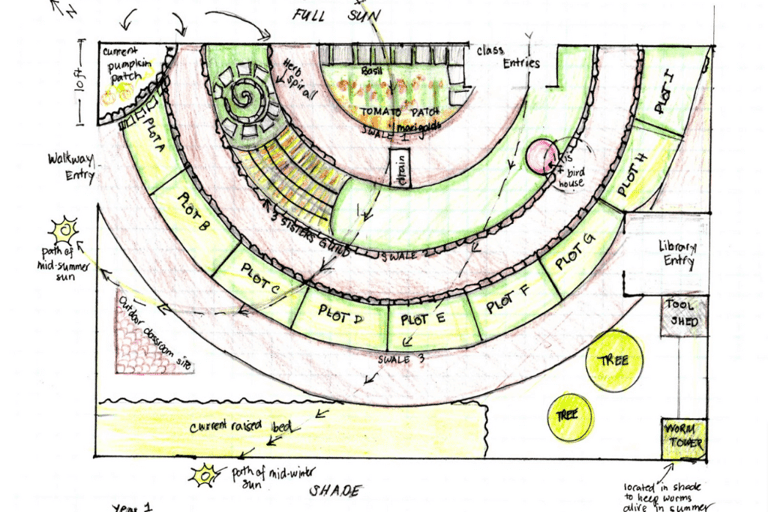

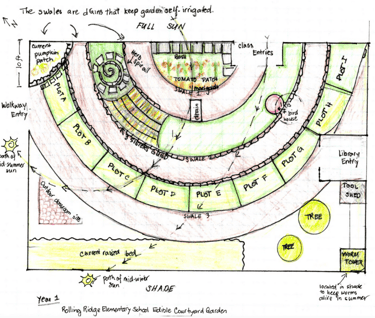

An early draft of a school courtyard teaching garden.

How to keep your garden from being trampled on

8. Ensure Proper Access

If you are starting from a blank canvas, meaning you have undeveloped land without any pathways or structures, now would be the time to determine the best place for your pathways, roads, and routes on the property. This is because you've assessed your property in terms of the more permanent scales, and you have a better idea of where to place such things.

More likely than not, your property already has existing driveways and paths. Is there any room for improvement in this area?

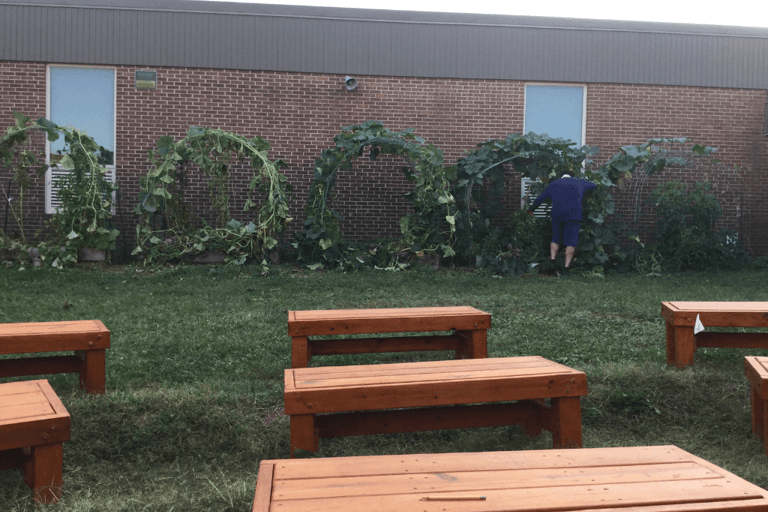

When I first started designing permaculture gardens, I created a school garden with as much growing space as possible. The problem was, that I didn't account for proper access.

As pretty as the design above may seem, it was not very practical, so we changed the design to include steps that went down to the “stage,” which cut through the curved raised beds. These steps were flanked with tree plantings to help absorb the water runoff that might flow down the steps.

School courtyard garden after garden installation.

What to Observe: Pathways

Observe patterns in your family's everyday actions especially as they walk to, from, and around your property.

Perhaps you’ve built a raised garden bed, but the dogs, chickens, or kids keep trampling on the vegetables. Should you impose your garden plan by encouraging them to use stepping stones or paths?

Should you block access to the gardens?

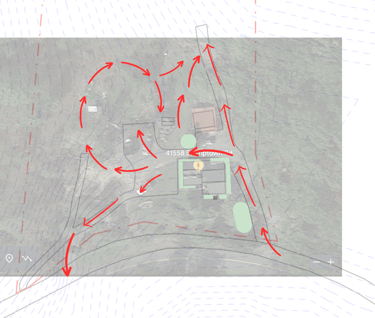

The red arrows show some of the paths that people to take as they move about our farm.

Find out first,

What is their pattern of movement around your property?

Is it easier to move the gardens or have the chickens, dogs, and kids change their behavior?

If you have a driveway leading to the house, can that driveway serve to channel water where you can store or capture it in the landscape?

In Arizona, Brad Lancaster initiated street “curb cuts,” so that water could slowly sink into the soil and be used to irrigate sidewalk gardens.

When I first started designing permaculture gardens, I created a school garden with as much growing space as possible. The problem was, that I didn't account for proper access.

As pretty as the design below may seem, it was not very practical, so we changed the design to include steps that went down to the “stage,” which cut through the curved raised beds. These steps were flanked with tree plantings to help absorb the water runoff that might flow down the steps.

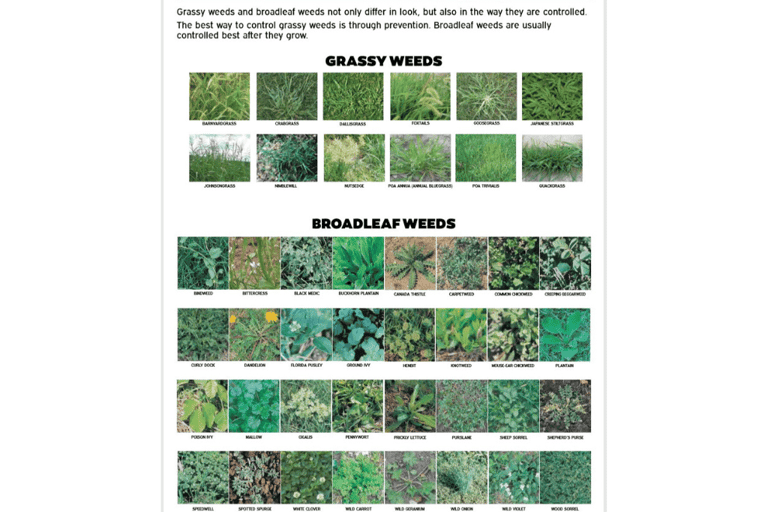

Taken from ChemJoe.com

Plants as bioindicators

9. Investigate the Weeds

Because weeds are "solving soil problems," they can also tell us what type of soil we currently have.

Prostrate knotweed (Polygonum aviculare), Purslane (Portulaca oleracea), and Red sorrel (Rumex acetosella) for instance, grow in acidic soils.

Chickweed (Stellaria media or Cerastium spp.), and chicory (Chicorium sp.) on the other hand like rich soil that's already high in nitrogen. These two weeds grow well in alkaline, compacted soil. So if you have chickweed and chicory already growing in your yard, they serve as bioindicators of the soil. Many weeds like chickweed, chickory, and purslane, also have the bonus of being edible not just to chickens, but to us!

Here's some research on weeds in North America and their soil bioindications.

The existing vegetation on your property can give clues as to how nature is trying to solve the current problems on your property. As the plants grow they interact with the life in the soil and modify soil structure. As nature gets to work in this way, it balances things out. The plants that first colonize a troublespot, are known as "pioneering species." They grow but as they change the soil profile for the better, they make room for other types of plants to flourish. We know these pioneers by another name: "weeds."

Sometimes, weeds grow because there’s a disturbance in the soil that nature wants to fix. Is your soil crumbly and dry? Usually, weeds with fine net hairs to keep the soil in place will grow in that spot. Is your soil compacted and clay-y? Then weeds that grow there will send down deep taproots that try to break up the clay as it grows. We need to notice these subtle (and not-so-subtle) “nature nudges,” and take our cues from them.

Plants as bioremediators

Plants as nutrient-managers

The old way of soil science relied heavily on testing for the presence or absence of chemicals in the soil. This was good, but discounted the fact that some minerals, though present via soil test, could still remain locked up and unavailable to the plants that needed these nutrients.

Pioneering plants are especially good at managing, storing, and distributing these nutrients so that not only do they benefit themselves, but the soil and the plants around them do as well. How do they do this? Oftentimes, these plants have deep taproots that mine the lower layers of the soil for nutrients and bring them up to their leaves. When these leaves drop and decompose, they are natural fertilizers and make previously unavailable nutrients, bio-available to surrounding plants.

These “weeds” that are particularly useful in fielding nutrients are called "Dynamic Accumulators" in permaculture. The late ethnobotanist Dr. James Duke of the University of Maryland captured the nutrient uptake of these plants in his book The Green Pharmacy and this spreadsheet.

What to Observe: Weeds

Now that you know that your weeds can tell you more about your property, ask yourself:

Where are the pre-existing plants or trees located? Especially the ones that seem like nature planted them?

What weeds are currently growing in your yard?

Vegetation & Climate

One final note about vegetation and its relationship with climate: Think about where you can place plants and trees so that they can buffer the wind, store water, and increase biodiversity. These and many other functions are discussed in more detail when you intentionally design "permaculture guilds."

A book on this subject is Ehrehnfried Pfeiffer’s “Weeds and What They Tell Us.” This is a quaint read about weedy plants and their uses from the 1950s.

Thomas Elpel’s "Botany in a Day" is another great resource for learning about plants. The book is easy to read and you come away understanding which plants belong to which basic plant family

We would be remiss if we didn’t mention the master of field guides Roger Tory Peterson. So grab a Peterson Field Guide if you don't already have one.

Books on Weeds

Before you pull out your weeds,

find out what they are telling you.

The green beds show some planting areas. The multi-colored bins are where I would like the recycling and composting to go.

The Power to Choose a More Effective System

10. Placing Your Structures

As a homeowner or renter, you likely have smaller on-site problems such as:

Our family does not have a good way of composting or recycling. We just throw everything in the trash.

Problems like these can be solved with thoughtful structural additions or redesigns.

If you intend to do outdoor composting, where would the best location for a compost bin be? Remember, it should not be too far from the house that it deters you from composting. At the same time, it has to be a composting system that doesn’t attract rodents.

Our problem in our old townhouse was that we could not do any outdoor composting in open pallets.

To protect from rodents, we encased the compost area in wire mesh. This enclosure was helpful at first but not enough to deter animals. Even a hawk once got caught in our compost bin.

In the end, we settled for an enclosed compost tumbler system. We placed it close to the house so we could access it.

Currently, on our farm, we have room for open pallet composting. We want to consolidate or zone all three main bins: compost, recycling, and trash into one location.

One of permaculture’s principles is to “Integrate Rather than Segregate,” so having the main disposal bins together makes sense. Hiding the bins from an immediate view also makes sense from an aesthetic point of view.

Create a general theme or area based on what your place is telling you, which is what PA Yeomans meant by creating “Subdivisions.”

Perhaps as homeowners or renters, we do NOT have control over this part. The builders do. We just buy or rent the houses or apartments. But if we are designing a farm from scratch the placement of your home, your barn, and your fields should be governed by steps one through nine. A good builder will take serious care of these considerations. Sometimes, “How many homes can we sell in this amount of space?” can be the deciding factor.

Buildings and Architectural Choices

An example of an overall spiral shape guiding the terracing and paths intended for the gardens on this property

11. Bonus Step: Aesthetics

Shape - What overall shape would you like to use in your garden? Is there one that you can use to make the entire garden cohesive?

Repetition of Pattern - Repeating specific plantings of the same kind of flowers or crops creates a visual uniformity and evokes peace and calm.

Scale or Proportion - Try to use dwarf varieties of trees in a small garden, and larger trees in big gardens.

Movement - To create interest in your space, it is good to consider the direction in which your eyes and body will move as they pan the landscape and eventually rest on a focal point.

Focal Point - A focal point helps the eye eventually rest on a central show-stopping tree or plant that unifies your visual panorama.

Balance and Diversity - A diverse planting scheme, instead of a monoculture, creates visual interest and beauty and balances out your ecosystem.

Harmony - You can achieve harmony when you apply "a pattern language," as discussed above.

Color - Consider the thematic color palette that you would like to use to create a visually stunning garden.

Elements of Design

Here are elements of design that can be incorporated in art, but also when thinking of your own permaculture property.

Dig Deeper

Observation is the foundation of permaculture design, guiding you to create a garden in harmony with the natural world. These "10 Crucial Steps" provide a structured approach to design, making the process easy to remember and fun!

As you embark on your permaculture journey, remember to observe, trust the process, and reap the fruits of your labor for years to come.

You can simplify the garden design process by using our SAGE garden designer and planner application. It's not only a vegetable garden planner, but also considers the role of:

Perennials

Pollinators or flowers,

Companion planting and

Your family's overall food goals in your garden layout.

It's bound to make your garden planning easier!

Happy gardening!

I WANT TO GROW MORE

Sign Up for a

Permaculture Garden Course

I AM A BEGINNER

I WANT MY DREAM GARDEN

Sign up for the

Grow-It-Yourself Program

Everything you need to start a garden

may be hidden in your pantry.

Take a self-paced, step-by-step garden course to help you grow right from seed to harvest.

Make Your Organic Food Garden A Reality with

a garden mentor

a community

an app &

a proven plan!

Choose one next step.

Which of the following are you?

Permaculture Gardens - your online resource for organic & sustainable gardens.

Contact

permaculturegardens@gmail.com

Bethany Farm

41558 Stumptown Rd.,

Leesburg, VA 20176